by Ana Paula de Oliveira Souzaa, Luana Oliveira Leiteb & Carla Forte Maiolino Molentoa

aAnimal Welfare Laboratory, Federal University of Paraná, Curitiba – Paraná, Brazil.

bFederal University of Paraná. Curitiba – Paraná, Brazil.

[DOWNLOAD ARTICLE] [Download complete PDF 6.2Mo]

To cite this article (suggested): Souza A.P.O., Leite L.O. & Molento C.F.M., « Animal welfare in Central and South America: What is going on? » [PDF file], In: Hild S. & Schweitzer L. (Eds), Animal Welfare: From Science to Law, 2019, pp.88-102.

Introduction

Animal welfare (AW) is a relatively new scientific and professional field. As such, it is expected that it be in an initial phase of development in many places. As a reference point to this understanding, we may consider the fact that AW was taught for the first time in a Veterinary School in 1986, as a course organized by Donald Broom in Cambridge University. Even though there is scarce information on the teaching of AW in Central and South America (CSA), it seems that there is a time gap of at least two decades compared to Cambridge University. In Brazil, for example, the first time an animal welfare course was taught to veterinary students was in 1999, at Universidade de Brasília (Molento and Calderón, 2009); few AW research groups started somewhat earlier, in the 80’s (Tadich et al., 2010). Thus, it is expected that major actions and regulations directed to AW are currently in their initial steps, yet to achieve robust, well-defined and stabilized scenarios in CSA.

Together with the research and teaching developments in Europe, important norms have been put forward. In 1978, the European Economic Community (EEC) approved the European Convention for the protection of animals kept for farming purposes, which was created mainly due to disparities between animal protection laws in different countries (European Economic Community, 1978). Updated regulations are:

- protection during slaughter, Council Regulation 1099/2009/EC (previous regulation Directives 74/577/EC and 93/119/EEC);

- protection of laying hens, Council Directive 1999/74/EC (previous regulation Directive 88/166/EC);

- protection of calves intended for slaughter, Council Directive 2008/119/EC (previous regulation Directive 91/629);

- protection of pigs, Council Directive 2008/120/EC (previous regulation Directive 91/630/EEC amended by Directive 2001/93/EC);

- protection of chickens kept for meat production, Council Directive 2007/43/EC. For further details, please see Veissier et al., 2008.

Globally significant efforts may be understood from some World Organisation for Animal Health’s (OIE) significant achievements:

- Since 2003, the publication of twelve global AW standards, covering issues such as transport, slaughter, control of stray dog populations and welfare in farm animals including fish;

- Organization of three OIE Global Conferences on Animal Welfare, in Paris, 2004, Cairo, 2008 and Kuala Lumpur, 2012;

- The publication of three special issues on AW, volumes 24, number 2, in 2005 and 33, number 1, in 2014 of the OIE Scientific and Technical Review, and volume 10 of the OIE Technical Series, in 2008 on the Scientific assessment and management of animal pain.

If changes in real life are related to developments in teaching and scientific research, what is the situation in CSA, where both activities are more recent in the field of AW? The question seems especially relevant due to the high number of farm animals used in CSA. It is also an intriguing question, since AW is a field where science is intertwined with cultural contexts (Fraser, 2008). In other words, the baseline from which knowledge and changes in AW may be built are likely not the same in different geographical regions. Thus, our aim was to study AW policies and initiatives in CSA, in order to improve our understanding of the current situation and to suggest strategies to overcome eventual obstacles for the development of better living conditions to farm animals in this geographical region.

Material and Methods

Our main method was a questionnaire sent to specialists in CSA countries. First we sent a questionnaire to professionals related to animal welfare issues in 20 countries, being them professors and researches in universities, OIE national focal points on animal welfare and professionals from governmental bodies on the livestock production sector. The questionnaire was built based on four main issues:

- current state of AW,

- social and cultural specificities that impact on AW,

- political will to improve AW and

- importance of European demands and directives for AW in CSA countries. We received replies from one respondent from each Argentina, Colombia, Suriname and Venezuela, and two respondents from both Chile and Ecuador; we added Brazilian data.

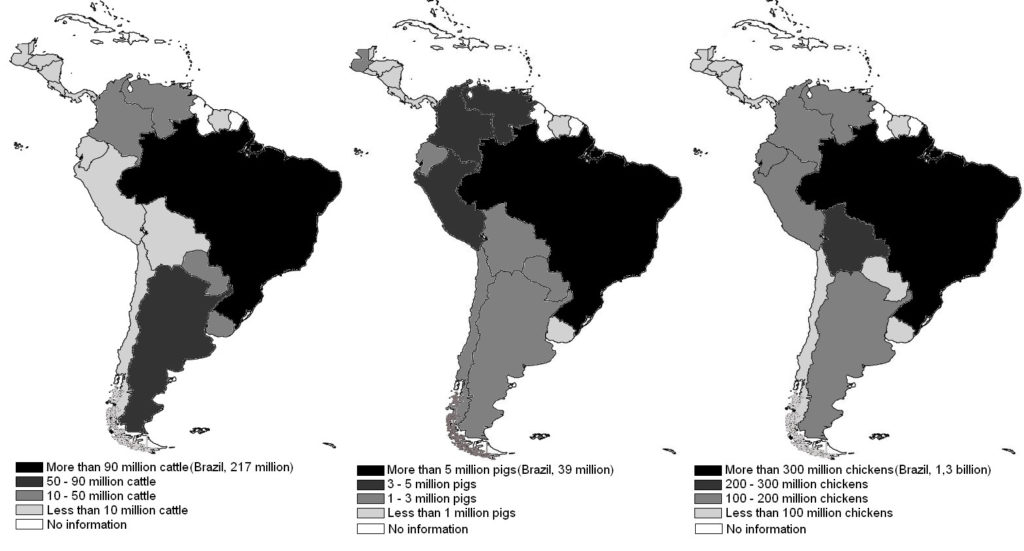

Of total CSA animal production, responding countries represent 85.5% of cattle, 77.3% poultry and 81.4% pigs, as calculated considering the statistics in the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations website (FAO, 2014). The distribution of farm animal population per country, in absolute numbers, is shown in figure 1. This high percentage of the total CSA animal production represented in only six respondents is due mostly to the high number of animals involved in the main production chains in Brazil.

Due to the fact that out of 20 countries contacted only six responded, we additionally searched AW regulation on governmental websites and on the websites of Animal Protection Index by the World Animal Protection (WAP, 2014), Global Animal Law (Global Animal Law, 2015) and Legal Office FAOLEX by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO, 2016). According to the information available, data was organized in the following three main categories of regulation: transport, slaughter and general animal protection law. To present as main results on Table 1, we also selected regulations that seemed to present a federal legislative identity, as opposed to lower level norms and good practice guides, which were abundant and to which it was difficult to ascertain a reasonable pattern for a balanced inclusion regarding all countries. The lower level regulations found are discussed in the text.

Additionally, we identified the five main countries in terms of number of animals involved in animal production according to FAO (FAO, 2014), considering beef cattle, poultry and pig statistics. These countries were Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia and Peru. In order to get a view about current AW issues relevant to local societies within these five countries, we searched for information regarding AW and animal protection on the two main newspapers of each country, between 2010 and 2015. The importance of each selected newspaper was based on national circulation numbers, and the words used to search information were animal welfare, animal protection and animal abuse, using the language of each country.

Data was analyzed by descriptive statistics.

Results

Results are organized according to the four main issues addressed in the questionnaire.

1. Current state of animal welfare

A historical view of animal protection laws in CSA is presented on Table 1. In South America, most countries maintain some reference to legislation on AW topics. We did not find information for French Guiana and Suriname, thus results are presented for 11 countries in South America (SA) and seven countries in Central America (CA). Animal protection regulation was found in 18 countries in CSA, representing at least minimum protection against animal abuse. The eldest legislation was found in Argentine, dating from the 19th Century. For Central America, the history of animal protection law seems more recent. In most countries, transport, slaughter and other issues directly related to farm animals are regulated by recommendation guides and regulations other than laws. It was difficult to gain access to specific regulations and we discuss here a combination of those mentioned by respondents and others we were able to find online. As a consequence, our presentation of farm animal welfare regulations is not exhaustive.

Respondents reported different levels of regulation for farm animal protection, transport and slaughter and the discussion is presented in alphabetical order. In Argentina, the Resolution 97/1999 regulates vehicles intended for animal transportation. In addition, according to the respondent from Argentina, the SENASA (Servicio Nacional de Sanidad y Calidad Agroalimentaria) developed a guide for animal welfare procedures, based on good agricultural practices.

In Brazil Regulation No. 575/2012, Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Food Supply (MAPA), regulates road transport of animals, with the production of technical material to qualify the actors involved in this production chain, and a corresponding Manual of Good Management Practices in Transport is currently available online (MAPA, 2016). Other guidance is provided by MAPA in Manuals covering Equine Welfare in Competitions, Care to Newborn Calves, Good Practices for Vaccination Procedures, for Animal Identification and for Milking Cows. As for slaughterhouses, regulations in Brazil, Chile and Argentina make stunning mandatory; however, there is exemption for religious slaughter in Brazil and Chile, employed to supply external market with this specific requirement. In Brazil, the Humane Slaughter Regulation 03/2000 includes mammals and birds; fish are not included. Even though the regulation is under review, fish will not likely be included due to lack of scientific knowledge regarding proper stunning for the most commonly produced fish species. The exclusion of fish species from humane slaughter regulations is probably the most common situation for CSA countries.

Table 1. Countries maintaining federal animal protection laws and year of publication; partial information as obtained online and complemented with information from respondents, 2015; other types of regulation are not included (please refer to text).

|

Continent |

Country |

Regulation |

Year |

|

South America |

Argentina |

Law 2786, prohibiting animal abuse |

1891 |

|

|

Law 13346, abuse act and acts of cruelty to animals |

1954 |

|

|

Brazil |

Decree 16590, public entertainment houses, prohibiting animal abuse |

1924 |

|

|

|

Decree 24645, for animal protection |

1934 |

|

|

|

Law 9605, for environmental crimes |

1998 |

|

|

Bolivia |

Law 4095, for animal protection |

2009 |

|

|

|

Law 700, for the protection of the animals |

2015 |

|

|

Chile |

Law 20380, for the protection of animals |

2009 |

|

|

Colombia |

Law 5, on Animal Protection Groups |

1972 |

|

|

|

Law 84, for the protection of animals |

1989 |

|

|

Guiana |

Criminal Law Act |

1998 |

|

|

Paraguay |

Protection and Animal Welfare Act 4840 |

2013 |

|

|

Ecuador |

Ecuadorian Criminal Code |

1999 |

|

|

Peru |

Protection Act 27265- pets and wild animals kept in captivity |

2000 |

|

|

|

Legislative Act 635, Criminal Code |

2004 |

|

|

|

Decree 1449, reorganize the Ecuadorian Agricultural Health Service |

2008

|

|

|

Uruguay |

Law 18471, for the responsible possession of animals |

2009 |

|

|

|

Decree 62, regulation of Law 18471 |

2014 |

|

|

Venezuela |

Criminal Law for the protection of livestock activity |

1997 |

|

|

|

Law 39338, for the protection of free and captive domestic animals |

2010 |

|

|

Central America |

Belize |

Cruelty to Animals Act |

2000 |

|

Costa Rica |

Law 7451on Animal Welfare |

1994 |

|

|

El Salvador |

Decree 661, Law for citizens and administrative contraventions |

2011 |

|

|

Guatemala |

Decree 22, Law for the control of dangerous animals |

2003 |

|

|

Honduras |

Law on Protection and Welfare of Domestic Animals, free and in captivity |

2015 |

|

|

Nicaragua |

Law 747 for the protection and welfare of pets and domesticated wild animals |

2011 |

|

|

Panamá |

Act 70, protection of domestic animals |

2012 |

Brazilian government, through MAPA initiatives with the collaboration of World Animal Protection, has been funding the development of material and courses around the country on humane slaughter of cattle, poultry and pigs, in a program that became known as STEPS (MAPA, 2016). This initiative has reached mostly abattoirs within federal inspection, which tend to be the biggest and technically most advanced ones and which sell to both domestic and external markets; those inspected by individual states or by municipalities have not been reached with the same intensity yet. Although other norms regulating organic production include AW topics, there is no specific regulation for on-farm AW in Brazil.

In Chile, there are two norms regarding farm animals: Decree 240/1993, on beef cattle transportation, and Decree 94/2008, on slaughterhouse operation. Based on Law 20,380/2009, three decrees were approved in 2013, by the Ministry of Agriculture, to regulate the protection of animals reared for the production of meat, skin, feather and other products (Decree 28/2013), the protection of animals during production and commercialization (Decree 29/2013), and the protection of beef cattle during transport (Decree 30/2013).

In Colombia, Decrees 1500/2007 and 2270/2013 establish standards of animal welfare during cattle and buffalo pre-slaughter operation. Resolutions 2341/2007, 3585/2008 and 2240/2007 are in place for the protection of cattle, buffaloes and pigs on farm and during transport. Additionally, Resolutions 240/2013, on humane slaughter of cattle, buffaloes and pigs, and Resolutions 241/2013 and 242/2013, on humane slaughter of broiler chickens, are in effect.

In Ecuador, between 2014 and 2015, there was a proposal to establish an Organic Animal Welfare Act (Ley Orgánica de Bienestar Animal – LOBA), which was included in the Organic Environment Code approved in 2016. According to the respondent from Suriname, the National Ordinance for the prevention and control of Animal Diseases, 1954, is in place for farm animals. It includes species such as cattle, horses, sheep and goats, pigs and poultry. Draft concepts of Animal Health Production and Welfare Act, and of a Slaughterhouse and Meat Inspection Act, are in preparation in this country, with FAO collaboration. In Venezuela, the general Law 39338 (Table 1) refers to municipal rules on slaughter and use of domestic animals for human consumption.

Respondents from all countries, except Argentina and Venezuela, considered animal transport and slaughter as priorities to be addressed. Transport and slaughter may be of concern for most respondents due to specific characteristics of a region or a country, such as long transport routes, roads with poor infrastructure and poor slaughter conditions (von Keyserlingk and Hötzel, 2014). In addition, concerns about the welfare of animals during slaughter is also motivated for economic reasons. Respondents also considered as priorities to be addressed the intensive poultry and pig production systems (Argentina, Brazil and Colombia), animal handling (Colombia and Ecuador) and consumer awareness of farm animal welfare issues (Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela). In general, these answers seem to be a consequence of the low level of development and specificity of animal welfare regulations in CSA. Answers may also reflect increased demand from segments of society for the protection of farm animals, as well as the discussion on protection of animals in other contexts such as companion and laboratory animals.

2. Sociocultural specificities regarding the treatment of animals

According to Coleman and Hemsworth (2014), low qualification of workers that handle live animals may lead to reduced levels of animal welfare and productivity, which suggests the importance of considering educational and training attention received by those who directly interact with animals in CSA. Some countries in South America have developed training programs on animal welfare through private initiatives, governmental and non-governmental organizations (NGO). In Brazil, the already mentioned STEPS Program aimed to train governmental inspectors, professors and slaughterhouse workers in animal welfare at pre-slaughter and slaughter. More than 5,800 people were trained between 2009 and 2013 (MAPA, 2013); the next plan is to reach people involved in live animal transport. Other Brazilian initiatives, such as the National Service for Rural Learning (SENAR), provide training on good agricultural practices to farmers and have potential in terms of animal welfare training, due to the infrastructure already in place. In Chile, respondents informed that there are regulatory requirements for training on production, transport and slaughter of animals; and there are accredited institutes to perform those trainings. According to the respondent from Colombia, there are several initiatives, such as the National Service for Learning (SENA) that is developing a national capacitation program, the National Cattle Producer Association (FEDEGAN), that developed a farmer qualification program, and the Pig Producer Association (ASOPORCICULTORES), that is developing training for transport. The group of Veterinary Science Investigation (CIENVET), from Caldas University, has trained employees from slaughterhouses and developed specific teaching materials. The respondent from Ecuador informed that there are trainings on good agricultural practices performed by a governmental body (MAGAP) and national producer associations. Additionally, the government of Ecuador is organizing an animal welfare committee, with representatives from government, producer associations and universities, to establish basic principles of animal welfare that will help on the development of specific regulation in that country. The respondent from Suriname informed that most trainings are organized by the Ministry of Agriculture; however, no specific training was mentioned.

Although many initiatives were mentioned by respondents, major challenges remain. In some countries, as mentioned by Argentinean and Venezuelan respondents, there is no official training program. Also, it is probable that in most CSA countries training to deal with contingency situations is urgent. For example, two facts in Brazil caused extreme animal suffering. In August 2015, 110 live pigs that were in transit to the slaughterhouse remained seven hours on the truck after it was involved a road accident. In October 2015, 5,000 beef cattle drowned when a foreign ship that was transporting the animals sank during a stop at a Brazilian port. On-farm regulations for contingency plans for situations such as lack of power, for instance, are also in need of improvement. Additionally, according to Chilean respondents, training is not diffused, there are few people officially trained and there is a lack of governmental training program for small farmers. This is likely the case in most CSA countries.

The OIE recommends that animal owners and handlers should have sufficient skills and knowledge to ensure that animals are treated in accordance with minimum principles of animal welfare (OIE, 2014). Those countries in CSA where efforts in terms of farm AW improvement were reported seem to have started actions in the areas of animal transport and slaughter. This may be related to the convergence between AW and economic benefits in these areas, in most cases. One major exception is the long-distance transport of animals by sea, which is characterized by extremely low welfare for the animals but seems to be profitable. The developments related to animal sea transport require attention for the intrinsic cruelty involved. On-farm AW improvements, where some changes may involve increased farming costs, seem to be a necessary follow-up.

Table 2 shows a summary of responses to the question What are characteristics of your country that you consider either positive or negative to AW? Some characteristics were commonly mentioned by respondents, such as pasture systems, long distances for animal transport and increased societal concern with AW and animal abuse. Respondents identified potential AW restrictions and perceived many positive factors.The respondent from Ecuador cited specifically the political will to improve AW, which is a major positive characteristic, since it may affect animals in varied ways. As is the case in Brazil, it is likely that a relevant weakness in most CSA countries is the difficulty with enforcement of laws and recommendations.

It is important to discuss results bearing in mind the low number of respondents. Thus, it is expected that issues raised on table 2 are not exhaustive. For instance, even though this issue was not raised by the Colombian respondent, it is known in AW literature that Colombia and Brazil are suitable countries to introduce high welfare farm systems in terms of their climatic scenarios and burgeoning specific research. This is the case with silvopastoril systems for beef cattle production (Broom et al., 2013; FAO, 2013). Additionally, it is known that at least in Chile and Uruguay, as well as Brazil, there are active farm animal welfare teaching and research groups. Finally, the participation of Chile and Uruguay in the OIE Collaborating Centre for Animal Welfare and Livestock Production Systems provides an opportunity of supranational structure to foster more organized and more significant AW developments in CSA.

Table 2. Positive and negative characteristics of each country in terms of farm animal welfare, according to respondents from seven countries in Central and South America, 2015.

|

Country |

Characteristics relevant to animal welfare |

|

|

Positive |

Negative |

|

|

Argentina |

Beef cattle mainly reared on pasture |

Only beef cattle reared on pasture; people either uninformed or not interested in other farm species |

|

Brazil |

Beef cattle mainly reared on pasture Climate adequate for free-range systems in most production areas Climate in Southern Brazil favorable to open-sided poultry houses, with natural lighting Broiler chickens and pigs are reared in vertically integrated systems, facilitating dissemination of animal welfare concepts and procedures through farmers Broiler chickens are reared in concentrated areas, closer to slaughterhouses Increase on society demand for action against animal abuse Animal welfare teaching and research groups |

Bad road conditions Long journeys for beef cattle Drought in Northeast Farmers and industries fear of sudden and unilateral enforcement of AW regulations by MAPA Variety of difficulties regarding the enforcement of regulations Cultural characteristics involving animal abuse, such as cock fighting (which is illegal for the whole country), different forms of rodeos, urban draught horse use (which is illegal in some municipalities)

|

|

Chile |

Broiler chickens and pigs are reared in vertically integrated systems, facilitating dissemination of animal welfare concepts and procedures through farmers Broiler chickens and pigs are reared in concentrated areas, closer to slaughterhouses Consumer concern about AW have increased Increased development of AW regulations |

Bad road conditions Land extension, leading to long journeys and the need of sea transport of beef cattle Low educational level of workers that handle live animals Low perception of animal sentience by general population

|

|

Colombia |

Increasing concern about AW Increasing rejection of animal abuse practices |

Long journeys Bad road conditions Lack of training for workers who handle live animals |

|

Ecuador |

Political will to improve AW |

High altitude Resistance to alternative production systems Resistance of organized groups, like cock fighting organizations Farmer associations afraid of sanctions due to animal welfare regulations Low educational level of workers that handle live animals |

|

Suriname |

Short distances to transport animals by land |

Rainy and dry seasons, high temperatures Remote areas need transport by water |

|

Venezuela |

High percentage of literate people in rural population |

Lack of education and information about AW issues |

In general, respondents informed that labels do not provide information about production systems and are deficient in conveying information regarding AW issues. This is increasingly important because ethical concerns about how farm animals are reared are increasing among consumers. Label can take different formats to inform about animal rearing conditions (Kehlbacher et al., 2012), since the majority of consumer is distant from animal production. In Brazil, MAPA approves and supervises product label in relation to compliance with the identity and quality standard specific for each animal product, but there is no obligation to inform about production system. Recently, the Brazilian Association of Technical Standards published the NBR 16,389:2015, on requirements for free-range chicken production (ABNT, 2015). Although this NBR includes information about the rearing system, slaughter and labeling, it has no legal effect; thus, additional action is still needed to enforce its application. According to Schnettler et al. (2009), 49.2% of respondents in Chile informed that they would like product labels to include information about feeding, transport conditions, slaughter, traceability and production system. The respondent from Suriname informed that consumers are becoming more aware about AW, and that there is an annual book festival were children from kindergarten to high school are informed about where their food comes from, focusing on AW. As this type of education moves forward, refined labeling becomes central. Evidences suggest that the rejection of animal products from intensive low welfare industrial systems increases as consumers become aware of animal life conditions in these systems (Bonamigo et al., 2012). Recent work in Brazil has also revealed inaccurate product information and inappropriate welfare-related information observed on regular products (Franco et al., submitted). Thus, there are different levels of complexity to the challenges related to AW, which will require a variety of planned actions to be improved.

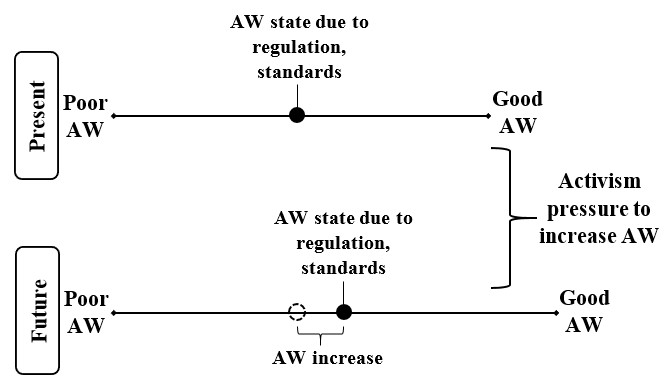

Vanhonacker and Verbeke (2014) observed that, since individuals are more interested in avoiding the bad than seeking out the good, communication about low animal welfare standards of regular products tends to be effective to increase the market for welfare-friendly products. In this regard, activism plays an important role to increase animal welfare standards. In Brazil, activism regarding farm animal welfare issues appears meager (Maciel, 2015), but recent campaigns aiming to inform consumers have been developed by NGOs. Two advertising campaigns have been supported by the Brazilian Vegetarian Society, “Why love one and eat the other?” and the “Meat-free Monday”. The Humane Society International, that has published news about animal use in laboratory and food production, recently started a new campaign on social networks to inform about battery cages used for most laying hens in Brazil. A common reaction to animal protection campaigns in Brazil, especially amongst people involved in animal production, is to try to disqualify their actions as radicalism. However, it is our perception that these campaigns have been important to change society views. Most defenders of common sense or so-called non-extremist approaches to animal protection may not realize how campaigns are important in shaping this perception of the reasonable way to act. It seems that there is a net effect in AW improvement as a result of the accumulation of activism and animal protection campaigns (Figure 2), and this may be observed both through tuning up discussions in each society as well as fostering law proposals and publications.

Low availability of welfare-friendly products is yet another important factor preventing consumers from performing their ethical choice on purchasing behavior (Franco et al., 2018). Most likely, availability of higher welfare products is a field to be explored in all CSA countries. All respondents considered alternative products, such as organic and free-range, scarce. In Brazil, according to Figueiredo and Soares (2012), the estimated annually organic production is 550,000 meat chickens, 720,000 dozen eggs, 13,800 beef cattle and 6,8 million liters of milk. According to one respondent from Chile, organic production has been developed there for 20 years and became regulated by Law 20089 in 2005, which set standards for organic production and the obligation of a certification seal, monitored by a governmental body (Servicio Agrícola y Ganadero de Chile). In Chile, few animals are organic certified, being them 624 meat sheep, 500 dairy sheep, 431 beef cattle and 22 dairy cattle (ODEPA, 2014). Free-range chicken products are also available in Chile, but lack specific regulation. According to the respondent from Colombia, alternative products have been developed as an opportunity to differentiate products, but this initiative remains marginal in the perception of producer associations. In Ecuador, animal production for subsistence is common practice, more common than industrial systems.

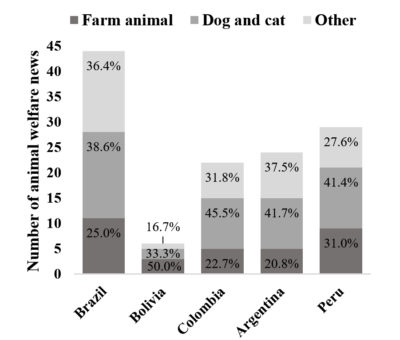

In order to consider the types of AW issues discussed in different CSA countries, newspaper information about AW in the five leading countries on animal production in CSA is summarized on figure 3. Absolute numbers are to be interpreted with caution, since the higher number of AW news in Brazil is probably due to the fact that the authors are more knowledgeable of Brazilian media than of the regular media in the other countries studied. If percentages of AW news regarding farm animals are observed, it is clear that this topic is present in the media in all five countries, in a significant proportion, standing as an issue close to companion AW news. The exception seems to be Bolivia, where news regarding farm AW appear in the highest proportion. Gonçalez (2015), studying the presence and type of approaches of animal welfare issues in Brazilian media specialized in rural journalism, observed that AW texts are increasingly frequent in rural technical magazines. However, most reports approached AW scientific developments and economic issues; topics related to animal ethics and AW policy were scarcely touched (Gonçalez, 2015). This fact suggests that within the environment of producers, field veterinarians and animal science technicians, the ethical questions that support the movement towards better lives for animals are borderline. Accordingly, it is our experience in participating in farm animal welfare committees in Brazil that there may be AW discussions where the interests of animals are overlooked. This situation could improve should animal ethics gain more visibility.

3. Political will to improve animal welfare

All respondents cited initiatives to improve animal welfare, specifically in terms of animal handling. According to Paranhos et al. (2012), in Latin America there are several initiatives being done to improve livestock animal welfare, with emphasis on the development of training programs and best practices. Respondents mentioned federal governmental bodies related to agricultural and rural affairs, except in the case of Venezuela, as responsible institutions for animal welfare regulation and inspection. In Brazil, the MAPA claims this responsibility. Further, this Ministry considers the AW recommendations set by the OIE as a standard basis to be followed by producers. Based on this, the Permanent Technical Committee on Animal Welfare has been working on the translation of the OIE Terrestrial Code to Portuguese. The standards on animal slaughter, beef and dairy cattle welfare are available on the official MAPA website (MAPA, 2015). In Venezuela, municipal authorities are responsible for animal welfare, according to articles 34 and 35 of the law for the protection of wild and captive domestic fauna (Venezuela, 2010); this fragmentation to municipalities may render it difficult to enforce animal welfare issues (WAP, 2014).

According to respondents, animal welfare committees have been implemented in different levels and with different participants. In Argentina and Venezuela academic groups have started discussions on animal welfare. In Brazil, the Permanent Technical Commission on Animal Welfare, MAPA, was created in 2008 and it has established animal welfare focal points in each one of the 27 Brazilian States. The Commission aims to coordinate the development of animal welfare policies in the country. In the State of Paraná, Southern Brazil, the Farm Animal Welfare Committee was established in 2014 to support the development of animal welfare policies for the animal production chains. Companies, farmers, cooperatives, universities, non-governmental organizations and continuing education institutions are represented. In Chile there are committees composed by industry, governmental and non-governmental bodies. In Ecuador there are some organizations (El Observatorio de Bienestar Animal, Comité de Bioética de la Universidad San Francisco de Quito) and the animal welfare advisory board of Agrocalidad (agency of agricultural quality assurance of Ecuador). In Suriname, the government organizes meetings with non-governmental organizations and private initiative. In Brazil, scientific groups working with AW seem a major power in the history of the developments in this area. The ETCO group at UNESP (São Paulo State University) and the LETA group at UFSC (Federal University of Santa Catarina) were pioneers in implementing some AW teaching and research around 30 years ago. Thereafter, other groups were formed, such as NUPEA and GEBEA at different campi of USP (University of São Paulo) and LABEA at UFPR (Federal University of Parana).

All respondents, except that from Argentina, informed of some level of farmer inclusion on political discussions about animal welfare, mainly through meetings. This approach seems to have superior chances of success, since it favors the consideration of these important stakeholders in the decision-making processes. In terms of the position of producers and the industry, some resistance to AW developments is apparent. Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Ecuador respondents informed that there is some funding, either governmental or private, to improve AW. It is probable that in most cases this funding is modest; however, its existence is a sign of the perception of AW as a relevant area for local development.

In addition to political will to improve animal welfare, demands from private sector about minimum animal welfare standards for food suppliers have also played an important role worldwide. According to Maciel (2015), large corporates are the main actors involved in the mobilization of resources for the establishment of new policy, through market laws. This is possible due to the emergence of standards for private schemes or product quality assurance schemes. The power of large retailers in demanding stricter standards of animal welfare is clearly visible in the United Kingdom (UK), where the Assured Food Standard scheme covers 82% of beef and dairy cattle producers and 90% of pig and poultry producer (AFS, 2012). Those numbers are in part explained by retailers demand in UK (Veissier et al., 2008). On the other hand, poultry welfare certification at farm level is scarce in Brazil, reaching only 2.1% of farms (Souza and Molento, 2015). It is likely that AW certification schemes in other CSA countries are scarce as well.

From a scientific point of view, when assessing AW in the current systems in Brazil, some priorities emerge in terms of policy. First, there are natural welfare advantages in farm animal welfare due to the characteristics of local production systems, so the lack of proactive regulation cannot be assumed to mean that AW is lower as compared to countries were regulations are in place (for example please see Souza et al.; 2015; Tuyttens et al., 2015). This, in turn, does not mean that farm AW is high; just the opposite, it may mean that the requirements included in European AW regulation are modest and would not represent real AW improvements elsewhere. The need for more information on local farm AW levels as well as local AW critical points is clear; only with this information strategies that will effectively improve the lives of animals in CSA countries can be planned and implemented. However, does this mean that the developments in Europe do not affect AW in CSA countries?

4. Importance of European demands and directives

How can we think about the importance of European demands and directives? There are, of course, direct effects due to the importance of the European market to CSA countries. All products sold from CSA countries to the European Union must comply with some European regulations, as the case of Regulations 2004/854/EC and 2009/1099/EC, for example. On the other hand, the adoption of European AW standards by CSA countries is showing some limitations and making the need for local AW research. Animal welfare-friendly certification schemes also slowly make their way to CSA countries, bringing welfare requirements higher than those in governmental baselines. The activities of European and other international animal protection NGOs also bring relevant changes to the life of animals in CSA countries. Many NGO proposals are sustained by the approval of European regulations.

According to respondents from Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Venezuela, the European Union is an important market. It is not the main export market of Brazilian broiler chicken meat; however, Brazil is the main supplier to the European Union (Van Horne and Bondt, 2013). About 60% of Brazilian beef meat exports go to European Union (Malau-Aduli and Holman, 2014). In Chile, beef and sheep meat were considered the main traded products, with mention to pork and poultry meat as well. According to Brazilian and Chilean respondents, companies authorized to export to European Union have adopted the European regulations that are required by the economic bloc. One clear example is the European regulation 2009/1099, which established requirements for the protection of animals during slaughter and demanded employees to be trained in humane slaughter procedures. In Brazil, the implementation of regulation 1099/2009/EC triggered off a series of training about humane slaughter, developed by the Ministry of Agriculture and World Animal Protection as mentioned above. In the same direction, Maciel (2015) observed that the development of farm animal welfare policies in Brazil resulted from external influence, mainly from the European Union and OIE. Similarly, one respondent from Chile informed that the government is working to harmonize the national slaughter regulation with the European regulation 1099/2009/EC, to facilitate international trade. In Colombia, the OIE recommendation was also mentioned as a standard to the development of animal welfare regulation.

Few respondents knew if there was any European animal welfare certification scheme implemented in their countries. One respondent from Chile informed that there are certification schemes in other areas, but not related to animal welfare. In Brazil, there are broiler chickens and beef cattle certified GLOBALG.A.P®, which is a farm assurance certification that includes sustainability, food safety, worker and animal health and welfare. Other certifications in this country are not from the European Union, as the case of the North American certification scheme Certified Humane®, which is implemented in broiler meat chicken, laying hen and dairy cattle farms in Brazil. However, North American certification schemes were not developed in isolation from European actions, so there is an evident indirect effect of European actions also in this case. In Suriname, GLOBALG.A.P.® is implemented for pig production.

As cited above, the adoption of foreign standards may have limitations to improve animal welfare. As an example, Souza et al. (2015) compared broiler chicken welfare in GLOBALG.A.P.® certified and non-certified farms in Southern Brazil and observed that farms complied with minimum welfare standards proposed by the certification scheme regardless of certification. Based on this, it seems that it is important to develop animal welfare protocols based on local characteristics of each country. The risks of assuming animal welfare effects of any regulation are also evident; animal welfare assessment is essential. Additionally, researchers in Brazil and Chile have applied the Welfare Quality® protocol, the former in broiler chickens and the latter in beef cattle, and both efforts led to the conclusion that the protocol should be reviewed to be suitable for production systems in these countries. There were difficulties to assess broiler chickens welfare in Brazil using the protocol, mainly on measures of plumage cleanliness, breast blister assessment, qualitative behavior assessment (Federici et al., 2015) and good human-animal relationship (Tuyttens et al., 2015). Respondents from Chile informed that the protocol was applied during its validation, in 2009, and as it was developed for confined animals, adaptations are needed to assess the welfare of animals reared on pasture. Thus, it may be concluded that refinements are needed. However, the possibility of having this discussion is due to the important investment in animal welfare assessment made by the European Union. It is clear that the European funded Welfare Quality project (Welfare Quality®, 2015) was a major asset for advancements in animal welfare assessment, has been the AWIN project (AWIN, 2015).

Advancements also stem from interactions between animal protection NGOs and the industry, through changes in consumer knowledge and opinion. Recently, BRF, JBS and Aurora, the three largest pork producers in Brazil, announced the abolition of gestation crates for sows in 2026, 2025 and 2026, respectively. Arcos Dorados, the largest McDonald’s franchise in Latin America, announced it will require its pork suppliers to submit documented plans in 2016 to limit the use of gestation crates for sows with plans for alternative group housing (Arcos Dorados, 2014). These changes are in line the Directive 2001/88/CE, setting off requirements relating to the welfare of pigs. The National Project for the Development of Pig Production (PNDS) and the National Fund for the Development of Pig Production (FNDS) were created to support pig producers in Brazil (ABCS, 2015) and may collaborate to transitions related to AW. This type of effort is welcome, since it recognizes producer vulnerability and offers viability for change to occur, which in the end tends to bring overall improvements and long-term strength to both producers and the production chain. Most importantly, when these efforts make change viable, they touch the lives of billions of animals.

Other example is the interaction between animal protection NGOs and the egg industry worldwide. As result, important groups have committed to eliminating the use of eggs from battery cages, such as Unilever, Nestlé, Starbucks and Grupo Bimbo. This international movement is reaching CSA. For example, in Brazil, the HSI created an online petition in 2015 to mobilize people to help end the confinement in battery cages. This initiative is in line with Directive 1999/74/EC for the protection of laying hens. Currently, the discussion on banning battery cages in CSA is not as highlighted as the one on banning gestation crates for sows. Local egg industry in Brazil remains more distant and perhaps resistant to this dialogue, a situation that seems similar to the case in the United States. However, from 2017 onwards the pressure for cage-free eggs has markedly increased in Brazil and it has succeeded in bringing together the industry, producers and animal protection, in a clear movement for change.

Maciel (2015) stated that external pressure started the development of AW policies in Brazil, but the actions tend to reach all markets, foreign and domestic. This is evident from field observation. Neighboring farmers do not remain untouched by changes when one of them adopts AW-friendly practices, be they due to a new certification scheme or a contract to sell to Europe. It is also not likely that a slaughterhouse will revert its practices back to a less efficient stunning practice because the next batch of animals is not meant to the European market. As AW improvements usually rely on training, they come to stay. The need for training also means giving more value to people, which tends to improve human welfare.

5. Moving forward

The intrinsic complexities of AW are logical, considering the scientific, ethical and legal dimensions of the field. In order to plan effective strategies for improvement, it seems interesting to employ the decision tree proposed by Ingenbleek et al. (2012). Each branch constitutes possibilities for developments and should thus be given consideration. The fact that certification may help in only specific knots deserves attention, since sometimes it is proposed as the major way forward. The tree also points out the importance of AW teaching, especially for veterinarians and other professionals involved with animals. If veterinary services are not well informed, the efficacy of regulations tends to be very limited. To the recommendations of importing knowledge, suggested by Ingenbleek et al. (2012), we add the development of a local network of teaching and research. The importance of this investment in local solutions lies in many factors. Minimally, people relate better to proposals when they were involved in their development, and their efforts to achieve goals are likely more genuine. Second, even though AW is an animal-centerd concept, there may be geographically localized specificities. For instance, when an outcome based thirst indicator was tested in Belgium and Brazil, it became clear that the results meant different things in each climatic condition and, consequently, should not be interpreted in the same way (Vanderhasselt et al., 2014). Scores of body dirtiness, an indicator of good housing in both Welfare Quality and AWIN protocols, may mean different welfare scenarios whether they are measured in indoor enclosures, and thus are related most likely to excreta or faeces, or on pasture situations, and thus potentially related to mud. Last, we can never overestimate creativity, and it is a good idea to invite researchers in different cultural contexts to think on solutions. The initiatives in South America on silvopastoral systems (Broom et al., 2013; FAO, 2013) are good examples. They constitute also another example of the importance of the interaction, as stated by the co-authorship of Donald Broom.

Lastly, we would like to repeat once again a very frequent statement in this text. The difficulties in gathering information were evident during the preparation of this work; they limit the generalization of our results, which may not be understood as a complete picture of AW in CSA countries. These difficulties are an obstacle to the development of AW actions and their tackling should be a priority if the goal is to achieve continental improvement. It is urgent to support the organization of information, as well as interaction to foster exchange of current status and of results obtained with different initiatives. Such interaction may create faster development, especially considering that there may be similarities in both characteristics and AW bottlenecks within CSA countries. Perhaps the existence of the OIE Collaborating Centre for Animal Welfare and Livestock in Latin America represents an advanced option to install a data collection infrastructure uniting the information, monitoring of AW regulations and initiatives and collaborating to strategic planning for the continental area.

Conclusion

It was difficult to obtain information about AW in the continental level; however, data obtained shows a real portion of farm AW status and initiatives in CSA countries. Animal welfare discussions, initiatives and norms are present in CSA, mostly in initial phases of development. Knowledge of local characteristics is highly relevant to understand animal living conditions and to create opportunities for improvements. A structure to constantly monitor information and support planned strategies to improve AW is welcome, including AW higher education and mechanisms for regulation enforcement. Central and South American AW issues other than those in farm scenarios remain to be studied.

To conclude, we acknowledge that we did not answer one initial question posed during the preparation of this paper: What is the importance of Europe demands and directives? It is difficult to quantify their importance to AW in CSA countries because all CSA developments are part of a chain of events and ideas that will, either directly or indirectly, connect to the European developments. We hope that Europe will propose increasingly higher AW requirements, for the good of animals in European and CSA countries. We also hope that the interactions across different geographical areas become closer and more frequent, and that CSA research and policy initiatives may increase their collaboration to make the world a better place for animals.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the respondents for their kind participation, especially considering the length of our questionnaire. We thank the animal science student Brunna Wagner from the Federal University of Paraná for compiling information from newspapers. We also wish to acknowledge that Ana Paula de Oliveira Souza is the recipient of a CAPES (Ministry of Education, Brazil) doctorate scholarship.

References

ABCS, 2015. Projeto Nacional de Desenvolvimento da Suinocultura (PNDS).

ABNT, 2015. NBR 16389:2015 – Avicultura – Produção, abate, processamento e identificação do frango caipira, colonial ou capoeira, 9p.

AFS, 2012. Red Tractor Assurance Annual Review. London, 24p.

Arcos Dorados, 2014. Arcos Dorados is committed to improved animal welfare in pork supply chain.

AWIN, 2015. Animal Welfare Indicators Anim. Welf. Indic.

Bonamigo, A., Bonamigo, C.B. dos S.S., Molento, C.F.M., 2012. Atribuições da carne de frango relevantes ao consumidor : foco no bem-estar animal. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 41, 1044–1050.

Broom, D.M., Galindo, F. a, Murgueitio, E., 2013. Sustainable, efficient livestock production with high biodiversity and good welfare for animals. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 280, 2013–2025. doi:10.1098/rspb.

Coleman, G.J., Hemsworth, P.H., 2014. Training to Improve stockperson beliefs and behaviour towards livestock enhances welfare and productivity. Rev. Sci. tech. Off. int. Epiz. 33, 131–137.

European Economic Community, 1978. Council Decision of 19 June 1978 concerning the conclusion of the European Conventon for the protection of animals kept for farming purposes. Luxembourg.

FAO, 2016. Legal Office FAOLEX.

FAO, 2014. FAOSTAT.

FAO, 2013. Enhancing animal welfare and farmer income through strategic animal feeding – some case studies, FAO Animal Production and Health Paper no. 175. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

Federici, J.F., Vanderhasselt, R., Sans, E.C.O., Tuyttens, F.A.M., Souza, A.P.O., Molento, C.F.M., 2015. Assessment of broiler chicken welfare in Southern Brazil. Brazilian J. Poult. Sci., in preparation.

Figueiredo, E.A.P., Soares, J.P.G., 2012. Sistemas orgânicos de produção animal: análise nas dimensões técnicas e econômicas, In: 49a Reuniao Anual Da Sociedade Brasileira de Zootecnia. Brasília, DF, pp. 1–31.

Franco, B.M.R., Souza, A.P.O., Molento, C.F.M., 2018. Availability and labeling of welfare-friendly food products and the opinion of retailers in Southern Brazil. Revista de Economia e Sociologia Rural, vol. 56, no 1, p. 9-18.

Fraser, D., 2008. Understanding animal welfare. Acta Vet. Scand. 50, 7p.

Global Animal Law, 2015. Database legislation

Gonçalez, F.B.T., 2015. Bem-estar animal na mídia: análise de uma década em revistas de jornalismo rural. 135p. Master Dissertation, Universidade Estadual de Campinas.

Ingenbleek, P., Immink, V.M., Spoolder, H.A.M., Bokma, M.H., Keeling, L.J., 2012. EU animal welfare policy: Developing a comprehensive policy framework. Food Policy 37, 690–699.

Kehlbacher, a., Bennett, R., Balcombe, K., 2012. Measuring the consumer benefits of improving farm animal welfare to inform welfare labelling. Food Policy 37, 627–633. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2012.07.002

Maciel, C., 2015. Farm animal welfare governance on the rise: a case study of Brazil, Public morals in private hands? A study into the envolving path of farm animal welfare governance. 160p. Thesis. Wageningen University, Wageningen.

Malau-Aduli, A.E.O., Holman, B.W.B., 2014. World beef production, In: Cottle, D., Kahn, L. (Eds.), Beef Cattle Production and Trade. CSIRO Publishing, Australia, pp. 65–79.

MAPA, 2016. Publicações.

MAPA, 2015. Recomendações OIE.

MAPA, 2013. Mapa e WSPA apresentam indicadores de sucesso com treinamentos em frigoríficos.

Molento, C.F.M., Calderón, N., 2009. Essential directions for teaching animal welfare in South America. Rev. Sci. Tech. 28, 617–25.

ODEPA, 2014. Agricultura orgánica nacional a junio de 2014. 9p. Santiago de Chile.

OIE, 2014. Introduction to the recommendations for animal welfare, in: Vallat, B., Thiermann, A. (Eds.), Terrestrial Animal Health Code. World Organisation for Animal Health.

Paranhos, M.J.R., Huertas, S.M., Gallo, C., Dalla, O.A., 2012. Strategies to promote farm animal welfare in Latin America and their effects on carcass and meat quality traits. Meat Sci. 92, 221–226. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.03.005

Schnettler, B., Silva, R., Sepulveda, N., 2009. Utility to consumers and consumer acceptance of information on beef labels in southern Chile. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 69, 373–382. doi:10.4067/S0718-58392009000300010

Souza, A., Molento, C., 2015. The Contribution of Broiler Chicken Welfare Certification at Farm Level to Enhancing Overall Animal Welfare: The Case of Brazil. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 1–19. doi:10.1007/s10806-015-9576-5

Souza, A.P.O., Sans, E.C.O., Müller, B.R., Molento, C.F.M., 2015. Broiler chicken welfare assessment in GLOBALGAP certified and non- certified farms in Brazil. Anim. Welf. 24, 45–54.

Tadich, N. A, Molento, C.F.M., Gallo, C.B., 2010. Teaching animal welfare in some veterinary schools in Latin America. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 37, 69–73. doi:10.3138/jvme.37.1.69.

Tuyttens, F.A.M., Federici, J.F., Vanderhasselt, R.F., Goethals, K., Duchateau, L., Sans, E.C.O., Molento, C.F.M., 2015. Assessment of welfare of Brazilian and Belgian broiler flocks using the Welfare Quality protocol. Poult. Sci. 94, 1758–1766.

Van Horne, P.L.M., Bondt, N., 2013. Competitiveness of the EU poultry meat sector. Wageningen.

Vanderhasselt, R.F., Goethals, K., Buijs, S., Federici, J.F., Sans, E.C.O., Molento, C.F.M., Duchateau, L., Tuyttens, F.A.M., 2014. Performance of an animal-based test of thirst in commercial broiler chicken farms. Poult. Sci. 93 , 1327–1336.

Vanhonacker, F., Verbeke, W., 2014. Public and Consumer Policies for Higher Welfare Food Products: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 27, 153–171. doi:10.1007/s10806-013-9479-2.

Veissier, I., Butterworth, A., Bock, B., Roe, E., 2008. European approaches to ensure good animal welfare. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 113, 279–297. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2008.01.008.

Venezuela, 2010. Ley para la protección de la fauna doméstica libre y en cautiverio. Gaceta oficial 39338 del 04/01/2010, Venezuela.

von Keyserlingk, M.A.G., Hötzel, M.J., 2014. The Ticking Clock: Addressing Farm Animal Welfare in Emerging Countries. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 28, 179–195. doi:10.1007/s10806-014-9518-7.

WAP, 2014. Animal Protection Index.

Welfare Quality®, 2015. Welfare Quality® Network.